Whhat is Repatriation?

- Collapse of the Japanese Empire and Repatriation

- The Soviet Entry into the War and Attacks in Manchuria

- Background to the Internment of Japanese People in the USSR

- Repatriation and Maizuru

- Repatriation Port: Maizuru

Hospitality of Maizuru

Repatriation Port: Maizuru

On September 28, 1945, the Japanese government designated the Port of Maizuru as one of the entry facilities for Japanese military and civilian repatriates. On October 7 the same year, the first repatriation ship entered the port, carrying army soldiers from Busan, Korea. In November, the Maizuru Repatriates Relief Bureau opened to offer services to repatriates and demobilized soldiers. Meanwhile, around 33,000 Chinese and Korean residents in Japan left for their home countries via Maizuru.

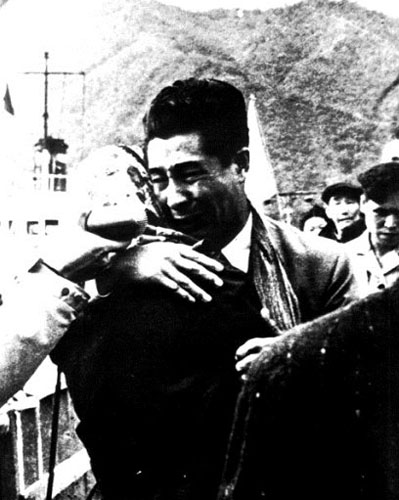

The first repatriation ship “Unzen-maru” entered the Port of Maizuru on October 7, 1945. From then on, residents of Maizuru offered various heart-warming services to console and encourage the repatriates, who were exhausted after the war and their long internment. For instance, residents welcomed repatriates at the port and served hot green tea and steamed sweet potatoes. When the repatriates left Maizuru to return to their hometowns, citizens also gathered along the road in the section from the Maizuru Repatriates Relief Bureau to Higashi Maizuru Station to see them off. The citizens’ warm hospitality delighted and inspired the repatriates, who had managed to outlive the calamities and returned home after a severe long journey.

Mrs. Hana Tabata: Mother of Repatriates

As the representative of a women’s group, Mrs. Hana Tabata welcomed repatriates, serving them hot tea and steamed sweet potatoes. Her service began with the entry of the first repatriation ship “Unzen-maru” on October 7, 1945, and ended with the entry of the last ship “Hakusan-maru” in 1958. She also visited repatriates at the Repatriates Relief Bureau to extend a hearty welcome and hospitality to the repatriates who had arrived at Maizuru. After the end of the repatriation project, she worked to build the Repatriation Memorial Park and the Maizuru Repatriation Memorial Museum, to pass on historical facts to future generations.

Mrs. Chiyoko Kimura

Mrs. Chiyoko Kimura was an instructor of flower arrangement. Upon the request of the Repatriates Relief Bureau at which her husband was serving, she began arranging flowers and occasionally serving tea to repatriates. She continued this service at the bureau until its closure in 1958. Even after the closure of the bureau, she continued offering flowers and tea in the Repatriation Memorial Park to console the spirits of the deceased who had died in foreign countries during and after the war. Her activities have been passed down until today in the form of peace memorial ceremonies.

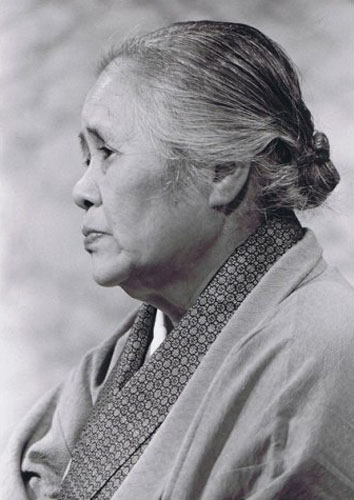

Mrs. Ise Hashino, known as “Gampeki no Hana” (Mother of the Quay)

Mrs. Hashino is regarded as the symbol of the “mothers on the quay.” To look for her only son, Shinji, who was on the list of missing persons, each time a repatriation ship entered the port, she came to Maizuru from Tokyo and stood continuously at the quay. The song “Gampeki no Hana,” which became a great hit in 1954, was composed with Mrs. Hashino as its model. On July 1, 1981, she passed away at the age of 81, believing that his son was still alive somewhere. Personal History of Mrs. Hashino

- September 15, 1899: Born in Hakui City, Ishikawa Prefecture. Moved to Hakodate, Hokkaido.

- Around 1920: Married Kiyomatsu, a crew member of the Seikan Ferry, who had married into her family.

- June 12, 1925: Her eldest son, Shinji, was born.

- Toward the end of February 1925: Her house was completely destroyed by a fire.

- Around December 1929: Eiko, her eldest daughter, was born.

- September 12, 1930: Her husband, Kiyomatsu, passed away.

- January 13, 1931: Eiko passed away.

- Toward the end of February 1931: Moved to Tokyo with her son Shinji. In Tokyo, she earned a living by dressmaking, serving as a housemaid and dorm mother for a factory, among other jobs.

- 1936: Moved to Omori, Ota Ward, Tokyo, where she continued to live till the end of her life.

- March 1944: Shinji departed to the field.

- Around August 15, 1945: Shinji’s comrade-in-arms announced that Shiji had been killed in a battle in China. However, she believed that her son was still alive, and repeatedly visited Maizuru when repatriation ships entered its port.

- 1956: Received an official announcement of Shinji’s death from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. However, she continued to await his safe return.

- July 1, 1981: Passed away at the age of 81.

Women standing on a quay in the Port of Maizuru, waiting for their husbands, were called gampeki no tsuma” (wives of the quay). Many such women took their children to Maizuru; some even settled in Maizuru.

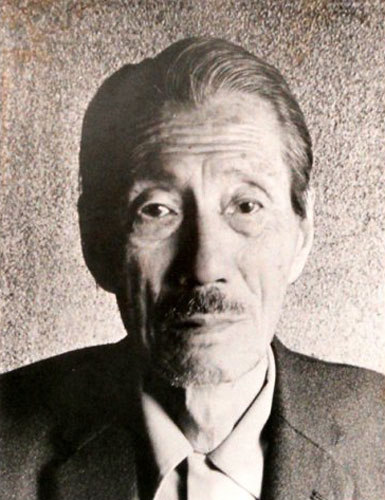

After the end of World War II, Mr. Eiichi Oki learned that his son, Haruo, had been taken away to Siberia. In hope of expediting the internees’ repatriation, he began a signature-collecting campaign at Umeda Station, Osaka, to send a petition to the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ). In the post-war Japanese society, engaging in such a campaign involved the risk of arrest, since it was considered an anti-social activity. Many people, nevertheless, sympathized with Mr. Oki’s cause. As a result, he was able to collect signatures from around 500,000 people, which he furnished to the GHQ and Ambassador Derevianko of the USSR. Even though his son, Haruo, returned to Japan in August 1948, he subsequently passed away due to malnutrition caused during the internment. Even after his death, Mr. Oki continued his campaign to realize the early return of internees from the USSR.

Mr. Niichiro Sakai: A Man Who Provided Information regarding the Safety of Internees

One summer day in 1948, Mr. Niichiro Sakai happened to learn that many Japanese internees were alive in the USSR when he was listening to Radio Moscow at his home in Kadoma (Osaka Prefecture). He took notes of the internees’ names and addresses, and sent postcards to their families to provide them with information about the internees’ safety. The recipients of these postcards were delighted to learn of the safety of their family members, and sent him letters of thanks. Some repatriates who had returned from Siberia also reported their safe arrival in Japan to Mr. Sakai.

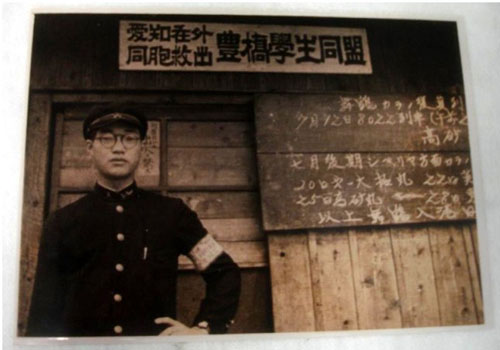

Before World War II, many Japanese students left their families living in Manchuria and other locations outside Japan in order to study in Tokyo, Osaka, and other large cities in Japan. After the end of the war, they were truly concerned about their families since there were no means of communication. Such students formed a student association to collect information from repatriates from Manchuria and other places. In addition to collecting information, these students helped repatriates in various ways: providing nursery care, assisting their transfer between trains, transporting and handing out relief supplies, and so on. They offered such services primarily at repatriation ports and terminal stations.

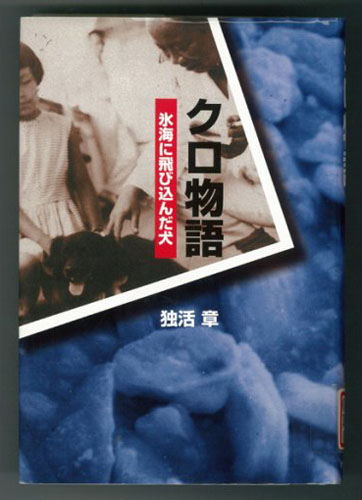

A dog called Kuro (meaning “black” in Japanese, since it had black hair) was kept by internees in the third ward of Khabarovsk labor camp. The female dog helped console the lonely people interned in such a distant place from their home country. When the last repatriation ship from Siberia—the “Koan-maru”—left the Port of Nakhodka early in the morning of December 24, 1956, Kuro dove into the icy water in the port to follow the ship. Passengers watching her swimming after the ship took her on board and brought her to Japan, considering her a friend who had shared with them the hardships of life in Siberia.